Scholars Foster and Gussow Unpack Race and the Blues | Music Reviews

Foster’s thoughtful and well-researched look at race and the blues will be useful to music and sociology academics; extremely knowledgeable but a bit overly academic, Gussow ably details the African American core of the blues and the shifting racial dynamics that have made the music so compelling

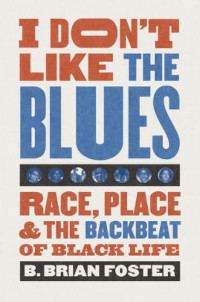

Foster, B. Brian. I Don’t Like the Blues: Race, Place, and the Backbeat of Black Life. Univ. of North Carolina. Dec. 2020. 208p. ISBN 9781469660417. $95; pap. ISBN 9781469660424. $24.95. MUSIC

Foster, B. Brian. I Don’t Like the Blues: Race, Place, and the Backbeat of Black Life. Univ. of North Carolina. Dec. 2020. 208p. ISBN 9781469660417. $95; pap. ISBN 9781469660424. $24.95. MUSIC

Foster (sociology, Southern studies, Univ. of Mississippi) examines the present-day, small-town rural South through a case study of Clarksdale, MS (pop. 17,725 in 2013), where blues icons Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker lived. He describes the recent attempts by Mississippi politicians to foster economic development in Clarksdale through blues clubs and festivals, which attract mostly white tourists. Interviewing nearly 250 residents between 2014 and 2019, the author found little interest in blues music among African Americans, who consider it the outdated sounds of the cotton fields that they would rather not revisit. Indeed, most African American residents, now 80 percent of the Clarksdale population, feel they have experienced the blues, which they define as racist-induced poverty and struggles that have led to a shared history and collective identity in the increasingly economically impoverished town. VERDICT Foster’s thoughtful and well-researched look at race and the blues via an exploration of a distressed and declining Southern rural town will be useful to music and sociology academics.—David P. Szatmary, formerly with Univ. of Washington, Seattle

Gussow, Adam. Whose Blues? Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music. Univ. of North Carolina. Oct. 2020. 336p. ISBN 9781469660356. $95; pap. ISBN 9781469660363. $28. MUSIC Gussow (English, Southern studies, Univ. of Mississippi; Beyond the Crossroads), a white blues harmonica performer/teacher, concert promoter, and music writer, stitches together a dozen rewritten YouTube lectures and three previously published articles to understand the current dominance of the blues scene by white artists. In somewhat meandering chapters, he describes the complex emergence of the blues at the turn of the 20th century through the innovations of mostly Black and a few white musicians; the distinctive musical characteristics of blues music and lyrics; and how an African American fear of white-perpetrated violence helped give rise to the blues form. Gussow spends the last section of the book on the development of blues literature by such pioneers as W.C. Handy, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and the writers of the Sixties Black Arts Movement. VERDICT Extremely knowledgeable but a bit overly academic, Gussow ably details the African American core of the blues and the shifting racial dynamics that have made the music so compelling to white Americans and blues fans in other cultures. Blues scholars will find the book illuminating.—David P. Szatmary, formerly with Univ. of Washington, Seattle

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!